“Soon after I entered upon the Presidency of the College, say near the end of 1846, the plan entered my mind of attempting to raise money to build a Cabinet. I was stimulated also by the offer of Professor C. U. Shepherd to deposit his collections here if a good building were provided.”

– Hitchcock on reasons for the Octagon, from “Reminiscences

The Octagon showed a new dimension in the College Row. The former strict, religiously zealous reign of Heman Humphrey showed in the Federalist architecture of the buildings. With the Octagon, a new trend emerged: science buildings were built first and then renovated into humanities or arts buildings afterwards (for example, Webster Hall, Fayerweather, the Octagon). In addition, buildings were becoming more specialized. The Octagon, as the Woods Cabinet, had a unique purpose. On the other hand, the attic of South was used as both a lecture room, a laboratory, and a sermon hall.

But why an Octagon?

Hitchcock was very interested in the works of Orson Squire Fowler, an Amherst graduate of the Class of 1834. Fowler was a public intellectual, writing 108 books on a variety of topics including heredity, maternity, temperance, and the his call to fame – phrenology. Phrenology was the leading pseudo-science of the mid-19th century. It claimed that by studying the bumps on a person’s head, it was possible to deduce their mental capacity and aptitude. Hitchcock was an avid follower of Fowler, who worked alongside his brother, Lorenzo Niles Fowler, in their Phrenological Cabinet in New York City.

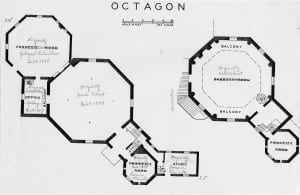

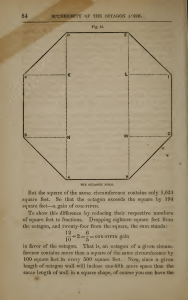

Among the 108 books that Orson Squire Fowler wrote lay the foundation of the Octagon – a book called “A home for all; or, The gravel wall and octagon mode of building.” In it he claimed that using an octagon shape for the base of a building instead of a square one would allow for a larger area usage with the same perimeter. Hitchcock, among other Fowler fans, gave rise to a now-bizarre trend of building octagon-shaped houses.

Here are some sections of the book showing the mathematical analysis of the use of the octagon base alongside the floor plans of the cabinet:

Hitchcock was enough of a fan of the Octagon that he added one as his study to his home on South Pleasant Street. Apparently, his personal study was located in the an octagonal addition that drew the quiet cabinet office space away from his boisterous six-children family.

The architect chosen for this project was Henry A. Sykes, a Springfield native. He agreed to Hitchcock’s polygonal bizarreness and used that to his advantage. After the Octagon’s successful reception, Sykes was called upon to design more specializes and unique academic buildings from campus that would also deviate from the Federalist, simple, rectangles of the College Row – Appleton Cabinet and Morgan Library.

(Click below to see images.)

Joseph B. Woods

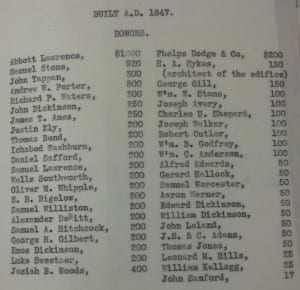

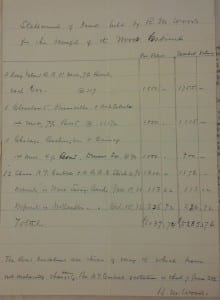

After his first failed attempt at gathering funds for the Octagon, Hitchcock received a generous offer from Joseph B. Woods to leave the fundraising to him. Woods achieved his goal – the funds for construction were met (a whole $9,000), and not one cent in debt (as Hitchcock would proudly proclaim). His generosity and hard work were honored with honor in the building’s name – Woods Cabinet.

Lawrence Abbot

Lawrence Abbot donated the most to the fund, a fact that gave him the honor of his name on the observatory. His proud amount of $1000 also earned him the top spot on the Woods Cabinet memorial marble slab, which has inscriptions of the donors to the building as well as their donated amounts.

Professor Charles U. Shepard

The first inkling of a commitment to a science cabinet came through the declaration of Professor Shepard – his donation of his mineralogy collection spurred the creation of the Octagon itself. His only terms of donation were that a new “fire proof building” housed them. After a Trustee vote to fund a science cabinet for this collection, Hitchcock began his search for funds. Shepard’s collection, which featured a full array of geological materials of the state of Connecticut and an assortment of meteorites, was lost after its last exhibition area, Walked Hall, burned down in the fire of 1882.

Professor Charles B. Adams

Professor Adams allowed for the Woods Cabinet to grow in scope. Upon his death, his entire zoological collection, featuring an extensive array of mollusks, fish, birds, reptiles, and other animals, was donated to the cabinet and created a new dimension in scientific learning on the Amherst College campus.

The white marble tablet … recording the fifts secured by Mr. Woods, is to me one of the most moving and one of the most precious possessions of the College.

– President Stanley King on the Memorial White Marble. It stands always with Hitchcock’s collections – from the Woods Cabinet to Appleton Cabinet to Pratt Museum to the Beneski, where it is currently on view.

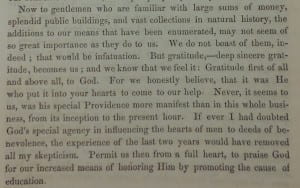

Click to see: the text for the memorial marble slab of donations; a receipt of the funds procured by Woods; a part of Hitchcock’s speech during the Dedication of the Woods Cabinet and Lawrence Observatory, on June 28th, 1847.